Most of Prof. Dawkins' uses of literally do not mean "word for word" or "in a literal as opposed to figurative way", but instead are a sort of intensifier. This is not at all surprising, since the emphasizing sense has been the commonest meaning of literally for a century or more, and Richard Dawkins is a very emphatic person. But all the same, I doubt that the legions of peevers who believe that literal should only be used to mean "not figurative" will even notice Prof. Dawkins' usage, much less work themselves into a froth over it. That's because his usage occupies a sort of middle ground, whose inconsistency with the "word for word" and "not figurative" meanings is subtle rather than blatant.

Consider how the entry for literally in Merriam-Webster's Dictionary of English Usage analyzes the semantic drift of literally. This narrative, which is not as well known as it deserves to be, follows the Oxford English Dictionary's entry through four stages.

The first … means "in a literal manner; word for word": the passage was translated literally. The second … means "in a literal way": some people interpret the Bible literally. The third … could be defined "actually" or "really" and is used to add emphasis. It seems to be of literary origin. […] The purpose of the adverb in [these] instances is to add emphasis to the following word or phrase, which is intended in a literal sense. The [fourth,] hyperbolic use comes from placing the same intensifier in front of some figurative word or phrase which cannot be taken literally.

In one instance, Prof. Dawkins uses literally in the first of this succession of meanings, "word for word" (or here "morpheme for morpheme"):

Theologians worry about the problems of suffering and evil, to the extent that they have even envented a name, 'theodicy' (literally, 'justice of God'), for the enterprise of trying to reconcile it with the presumed beneficence of God.

In a few cases, Prof. Dawkins uses literally with the second of these meanings, "in a literal (as opposed to a metaphorical, figurative or symbolical) way". In these cases, we could replace "literally" with "non-figuratively" or "non-symbolically" and retain the sense, if not the style:

[The enlightened bishops and theologians] may add witheringly that, obviously, nobody would be so foolish as to take their words literally. But do their congregations know that? How is the person in the pew, or on the prayer-mat, supposed to know which bits of scripture to take literally, which symbolically?

But in the great majority of the 38 examples in this book, Dawkins uses MWDEU's third sense of literally, meaning something more like "truly" or "precisely" — or simply "pay attention, now!":

A tree-ring clock can be used to date a piece of wood, say a beam in a Tudor house, with astonishing accuracy, literally to the nearest year. […]

And the amazing thing about dendrochronology is that, theoretically at least, you can be accurate to the nearest year, even in a petrified forest 100 million years old. You could literally say that this ring in a Jurassic fossil tree was laid down exactly 257 years later than this other ring in another Jurassic tree!

It's true that he means these chronological assertions to be literal rather than figurative, but it would be weird to substitute "non-figuratively" or "non-symbolically" or "non-metaphorically":

?A tree-ring clock can be used to date a piece of wood, say a beam in a Tudor house, with astonishing accuracy, non-figuratively to the nearest year. […]

?And the amazing thing about dendrochronology is that, theoretically at least, you can be accurate to the nearest year, even in a petrified forest 100 million years old. You could non-symbolically say that this ring in a Jurassic fossil tree was laid down exactly 257 years later than this other ring in another Jurassic tree!

?It is a fact that non-metaphorically nothing you could remotely call a mammal has ever been found in Devonian rock or in any older stratum. They are not just statistically rarer in Devonian than in later rocks. They non-figuratively never occur in rocks older than a certain date. […]

?There are non-symbolically no trilobites above Permian strata, non-metaphorically no dinosaurs (except birds) above Cretaceous strata.

When literally is weakened to "almost literally", it would be stranger still to substitute a denial of figurative, metaphorical, or symbolic intent:

The number of individual birds in these flocks can run into thousands, yet they almost literally never collide.

?The number of individual birds in these flocks can run into thousands, yet they almost non-metaphorically never collide.

It's easy to see how this purely-emphatic sense of literally turns into the hyperbolic sense, as it did by 1839 when Dickens wrote in Nicholas Nickleby:

His looks were very haggard, and his limbs and body literally worn to the bone, but there was something of the old fire in teh large sunken eye notwithstanding, …

And also:

"Lift him out," said Squeers, after he had literally feasted his eyes in silence upon the culprit. "Bring him in; bring him in."

The second of these quotes is in the MWDEU entry, as is the fact that the 1903 OED included a note by the editor, Henry Bradley, to the effect that literally is

Now often improperly used to indicate that some conventional metaphorical or hyperbolical phrase is to be taken in the strongest admissible sense.

It seems to me that the last quotation from Richard Dawkins, the one about how flocking birds "almost literally never collide", helps us to understand the transition from emphasis to hyperbole. Consider this passage from a recent restaurant review (Sam Sifton, "A Modern Italian Master", NYT 9/28/2010):

For the celebration of business deals, for instance, there is an enormous rib-eye, cooked to rosy perfection beneath a dusting of salt and pepper, with a pile of fried potatoes, a tangle of Italian arugula and dots of tomato raisins that are worth almost literally their weight in gold. (The dish is $130 à la carte.)

What does it mean to say that those tomato raisins "are worth almost literally their weight in gold"? The meaning here is surely very close to Bradley's diagnosis, "used to indicate that some conventional metaphorical or hyperbolical phrase is to be taken in the strongest possible sense".

And in fact, similar uses of the phrase "almost literally" are fairly common. There are 375 instances in the New York Times index since 1981, compared to seven instances of "almost really" and just one of "almost actually" ("Herb was almost actually bowled over by the thunderous roar of 'Surprise!'").

Rather, the meaning of "almost literally" in such examples seems to be something like "interpret what follows in the strongest contextually plausible sense, short of it being actually true".

This is different, I think, from the (much rarer) forms like "almost actually", "almost truly", and "almost really", which do have something like their compositional meaning, as in this case:

Steven Taylor, Far Beyond Forever, 2006:

It's hard to realize that it's almost really over and we'll be leaving this place for good in only one week.

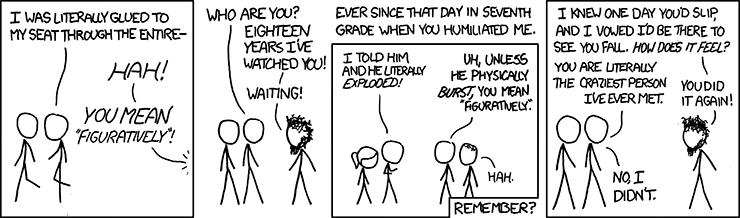

Now, lurking in the background of this discussion are the many people who get deeply upset over hyperbolical uses of literally. One of them is literally lurking in the background of this xkcd strip:

But as far as I know, none of these people has ever pounced on one of these "interpret in the strongest contextually possible untrue sense" uses of "almost literally". (I exempt Victor Steinbok, whose note about an example of "almost literally" on NPR happened to coincide with my perusal of The Greatest Show on Earth; as I understand it, Victor was observing rather than complaining.)

And now, for the few who are still with me, a final note about an unexpected connection between scripture and skateboards. NYT archive search generates "Related Ads" via Google AdWords:

Related Ads are links to keyword-targeted advertisements provided through the Google AdWords™ program. These links are purchased by companies that want to have their links appear with related search terms.

My search for "literally" generated Related Ads about bible study, which is hermeneutically straightforward. My search for "almost literally" generated Related Ads for skateboards. Can anyone explain why?

Update — for another pre-Dickensian hyperbolic literally, see William Robertson, History of America (Volume I), 1777:

The Andes may literally be said to hide their heads in the clouds; the storms often roll, and the thunder bursts below their summits, which, though exposed to the rays of the sun in the centre of the torrid zone, are covered with everlasting snows.

This strikes me as a perfect example of an adverb "used to indicate that some conventional metaphorical or hyperbolical phrase is to be taken in the strongest admissible sense". Note that Ben Zimmer took it back to 1766 in "Literally: A History", LL 11/1/2005; and I take it back to 1759 here…

Source: http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=3007

No comments:

Post a Comment